Let's start with a look at the old town centre. In Germany, they mostly date back to the Middle Ages. That sounds boring, but it's important to understand - because we're not starting from scratch anywhere in Europe.

In principle, the medieval town was organised like a supermarket today: the customer comes in at the gate. He walks on foot and pushes a trolley in front of him. Behind the entrance, everything had to be organised so that he could find his way around as quickly as possible and without a map: Here the vegetable counter, there the meat counter, there the bread counter, etc. Everything should be within walking distance and organised by theme. It was the same in the medieval town: the bakers were in Bäckergasse, the butchers in Metzgergasse, the tanners in Gerbergasse, the dyers in Färbergasse. Chickens were at Hühnermarkt, cattle at Rindermarkt. Everything had to work by word of mouth without a plan. There was no telephone, paper was unknown or far too expensive to be scribbled over with everyday information. Even a modern supermarket has to function without a plan or a smartphone. They are the last places in the city where people still ask for directions verbally. "Excuse me, where can I find the sultanas here?"

Personally, it always seemed illogical to me why all the bakers in the old town centres gathered in one alley just to compete with each other! But in a world with shadowy maps, everything had to be organised in such a way that it could be found by word of mouth. In addition, the tax had to be collected without a lot of paperwork. So the address "Bäckergasse 3" was also the VAT identification number. In this way, the tax authorities could be sure that everyone had been fleeced.

But probably the most important reason was another: the citizens had to put up with each other's emissions. If, for example, operations started at three in the morning in Bäckergasse and the ovens were stoked up, the neighbours couldn't complain because they were doing the same. No tanner could accuse his neighbour of preparing animal skins with urine, as they did it themselves. In this way, the city administration kept the neighbourhoods quiet. Furthermore, in times of epidemics, the authorities had to issue measures that had to be announced and monitored. The tradesmen did this for each other.

The disadvantage of this order was obvious: if ten competitors were crowded together, the only way to do it well was to agree on prices. Woe betide anyone who knocked a fiver off the price of bread! It's like the fairground today: candy floss costs the same everywhere. Or like today's model housing estates: Houses cost the same everywhere. There are enough customers.

The idea of distributing a city's bakers across the entire city layout may have seemed absurd to medieval people. It was about as logical as the suggestion to spread the bread range over the entire supermarket! "That's great! You won't find anything there!" And if you can't find anything in the supermarket - even the philosopher Robert Habeck gets angry!

Medieval towns were organised like well-stocked supermarkets selling everything the world knew at the time. The alleyways were narrow because retail space was precious. So the modern supermarket is the rebirth of an old town. Unfortunately, the city wall is now built with sandwich panels in corporate colours and the tower above it displays petrol prices. Or it invites you to stop off at the "Zur goldenen Möwe" inn.

So today we see how the retail space of an entire historic city centre is concentrated in one supermarket. It was a similar story with the shopping malls: Here, entire shopping streets were combined into arcades - including a "plaza" with a fountain, light theatre and "Venezia" ice cream parlour. Two examples of urban space becoming interior design.

In fact, the modern interior design was inspired by the historic city. It works with galleries, galleries, open staircases, landings, shelters, staircases and staircases. But this already existed in historical urban spaces. Bistro kitchens and bar catering already existed in the city around 1900, and even posters on advertising pillars have found their way into our homes. Before the modern age, it was not common to hang posters of concerts, artists or vernissages in your own home. Today, they can be found in every city flat. One could therefore venture the hypothesis that modern interior design is fuelled by the vocabulary of a northern Italian city. This is not a bad thing - on the contrary: it is evidence of an exchange from the outside to the inside. We can therefore speak of an internalisation of urban space in the 20th century. If we want a living city that is more than just the trick scenery of a car scene in a film, we should ask ourselves a question:

If interior design is a continuation of urban space by other means, can it also be the other way round?

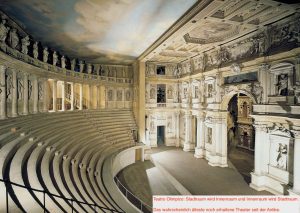

If you want to understand this, you have to do something terribly unfashionable and study the Renaissance architect Palladio. The "Teatro olimpico" in Vicenza is one of his last works. The maestro packed a message into this building - something I still think about a lot today. For some colleagues, this may be early baroque nonsense - for me, the building was one of the most important lessons about architecture ever:

Interior design is the continuation of urban planning by other means. /

Urban planning is the continuation of interior design by other means.

A living city is indistinguishable from a stage set. Good directors all understand something about cities and architecture, because they deal with the language of images, perspective, the depth of space, the play of light and shadow and the expression of the human face. They work with galleries, galleries, open staircases, landings, shelters, staircases and staircases.

If we want to leave something behind in the urban planning history of the 21st century that does not brand us as collectively stupid and affluent, we need to reflect on a few points. These texts may help you to work through these points.

This concludes the first instalment of this series, as the elaboration of these points will take time, material and consideration. In the meantime, the author recommends his essay: "Urban density through perimeter block development", a work from February of this year.

Further information on Palladio's Teatro Olimpico and the Renaissance stage design can be found in a work by the author from 2010.

In addition, of course, the author's book "Vom Greifen und vom Begreifen" from 2013, published by the author himself.

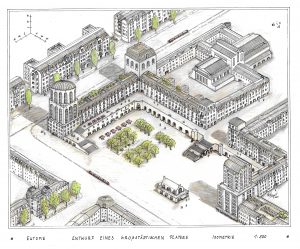

Finally, the author would like to show you four European examples that have taken this lesson to heart: The outer walls of the houses are the inner walls of the city. The streets are their corridors, the squares their rooms. The architecture is merely the provision of immobile pieces of furniture (French: immeubles, Italian: immobile).

***

First published on Facebook on 21.03.2021

Pictures:

Addendum:

210321 Addendum collected